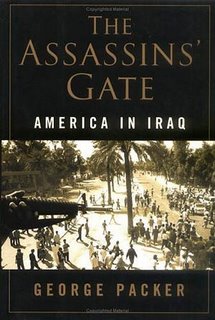

Iraq is a place of terrible sadness and terrible hope.

That at least is the lesson I take away from reading Packer's book, about the American invasion and occupation of Iraq. I found his book to be highly educational, engrossing, saddening and deeply moving. Packer does more than offer just an overview of the history of the invasion and the present occupation; rather, he attempts to get in the heads of both principle actors and ordinary people, Iraqi and American, swept up by the war and it's aftermath. In that way, he gives us a picture of Iraq, and ourselves through the lens of Iraq, that is as complete as it can be in one book.

Packer's book is divided into four different section. In the first, he talks about the run-up to the inavsion. This story we are mostly familiar with, as a result of countless news and magazine articles and interviews detailing the failure of the Bush administration to understand what they were getting us into, and plan accordingly for the consequences. But Packer takes us deeper into the motivations of those who planned the war, into the incredible insularity of President Bush and the willingness of the neo-cons in the administration to deny the complex realities of Iraq to further an airy ideal of democratization, while at the same time justifying to the public the need for invasion on national security grounds that they themselves didn't accept or were simply uninterested in. Through him we see how those in the administration

deliberately avoided planning for the aftermath of Iraq, believing that to do so would weaken their case for war and that it was entirely unecessary anyway. The neo-cons sincerely, honestly believed that a relative handful of Iraqi exiles, many of whom hadn't been in Iraq in decades, could lead the democratic revolution they had in mind, install a new government in a span of months that would be friendly to America as a result of the liberation, and allow us to pull our troops out before the end of the year.

Packer glosses over the invasion, and for good reason, as many would probably agree that though the initial invasion was the turning point for everything, it's also dwarfed by what's happened since. Instead, the next section of his book takes us inside first the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance led by Jay Garner, then the Coalition Provisional Authority under L. Paul Bremer. The failure of the ORHA is well documented; after all, Garner wasn't replaced after only a few months because he was enjoying wild success. But the simple truth is that Garner and the ORHA were set up to fail. They were not tasked with doing what would be necessary in Iraq after the invasion, because nobody believed that anything other than acting as a caretaker until the exiles could come to power was necessary. The looting and chaos that followed the invasion resulted in a quick change of plans, the sacking of Garner, and the creation of the CPA. But the CPA was also hampered by the failure to plan for the post-invasion period; planning was done on the fly in Iraq and in the Washington, and the officials working for the CPA, famously insulated from the world of Iraq around them, made decisions that seemed arbitrary, or uninformed, or capricious to the Iraqi people. Pronouncements were made that were aimed to the Americans back home, but real progress on the ground was hampered by key strategic mistakes such as widespread de-Baathification at the behest of the exiles and the neo-cons, economic changes put in place by young men and women from such places as the Heritage Foundation or the AEI, and the decision to completely disband the Iraqi army, a decision made seemingly by Bremer himself without any historical justification or guiding princples.

Far removed from the Green Zone, we then see a portrait of an American captain working on the ground with the Iraqis to furhter the reconstruction. Unlike the ideologues in the CPA, or even senior commanders in Baghdad or the Pentagon, American soldiers on the ground were interested only in what worked. How should they deal with the Iraqis? How can local government be reconstituted? Where can they get the money for reconstruction projects? American soldiers faced the double task of trying to fight a burgeoning insurgency without alienating the Iraqi populace, while at the sime time scraping for funds and equipment to do things they were never trained for like build schools or hold local council elections. Nothing if not resourceful, many of our soldiers did they best they could with what they could get their hands on, even as they began to die in greater and greater numbers.

But perhaps the most engrossing part of the book is the part about the everyday Iraqis themselves. Packer talks to Sunnis and Shiites, Kurds and Turkommen, former Baathists and former resistence fighters, the religious, the secular, insurgents and members of the militias, men and women. Through it all there emerges of a portrait of an Iraq that is chaotic, violent, backwards, but yearning for change and who all seem to start out cautiously optimistic about the future, though each Iraqi he talks to seems to have a different idea of what that future should or will be. But at the same time it is moving and saddening to read about how the violence worsens with each of Packer's return trips to Iraq, and how his Iraqi colleagues and friends begin to grow more and more fearful of the future, and more fatalistic, more resigned to a future of bloodshed, fighting, and chaos as Iraq begins to tear itself between the Kurds, Sunni insurgents and jihadists, and increasingly brutal Shiite militias. As you read, it's as if you can feel the hope draining from them, and their resignation as they realize they are trapped in a land that is still defined largely by the ways in which Saddam Hussein terrorized, brutalized and divided his own people to maintain his power.

The most painful chapter to read, "Memorial Day", is the story of a father who has lost his son, a private in the U.S. Army, to the war in Iraq. It is agonizing to read not only about the father's pain, but his unending questions about the war in Iraq that he is constantly asking. In an email, he candidly and honestly puts these questions to Packer, and to himself:

October 4, 2004: What is best for America and Iraq? That is the question. A better Iraq? Is it possible? Why did we go into Iraq? What justifies our remaining? American lives have been lost, precious lives, for what? Can something be achieved that is worthy of the sacrifice? Are there things not known to anyone other than the President and his advisors? No one in the Senate or any of the "attentive" and "informed" organizations? That would justify the sacrifice? And how much more sacrifice can be justified? For us to turn Iraq over to civil war would be hard to take. I don't have the right to advocate continued involvement because of my sacrifice that would lead to more, many more. What is best for America and Iraq? What is reality on the ground in Iraq? What is possible to achieve? Can Kerry and a team of his choosing do it? It is a great leap of faith. And most of the time none of this matters to me. I want my son. My son.

Packer doesn't have to say it, because it's clear from the fact that he included this and other agonized emails from the father. This father who lost his child in Iraq, is asking the questions that each of us should have been asking from the beginning, should have been asking this whole time, and should be asking ourselves now. The point is not primarily the answers, though we desperately need answers of some kind. The point is in the asking, because we can never even hope to come close to the answers unless we ask these questions honestly of ourselves, without consideration for which political party it harms or benefits. It shouldn't have taken the deaths of hundreds of soldiers to begin asking the questions, and it shouldn't require the deaths of thousands more to ask them in earnest now.

The book ends with the dissolution of the CPA and the national elections at the beginning of 2005, and Packer returns largely to the Iraqis that he's come to know to end his story. We see the elections were a hopeful event to many Iraqis, however they were interpreted by both sides here at home, but also that many Iraqis faced death to vote in a country that should have been well on its way to peace, and that many other Iraqis seemed willing to place themselves in the hands of Shiite political parties that want an Islamic theocracy that has little room for the Sunnis, secular Iraqis, and former Baathists. And as we've seen in the last year and a half, there are precious few ways in which anyone could say Iraq has gotten better. More and more Iraqis die, American casualties no longer make headlines because they're so common place, and hard-line Shiite militias seemed poised to wrest control of the country to themselves. Still, Packer's book gives us valuable lessons on what has happened-on what

is happening-in Iraq, lessons that we can use now, lessons that we ignore at our peril.

Pick it up.