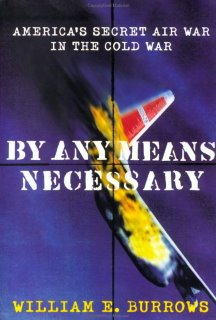

At the beginning of his book "By Any Means Necessary: America's Secret Air War in the Cold War", William E. Burrows quotes the famous scientist and "father" of the atomic bomb Dr. Edward Teller, who said in an interview with the NY Times in 1999 "The cold war had the distinction of not costing any lives." This of course could not be further from the truth. The cold war in fact cost many lives, both in the proxy wars that the United States and the Soviet Union fought that killed millions, but also in shadowy battles between the superpowers themselves, on dark street corners, on tense borders, under the oceans, and as Burrows writes about, in the dark and hostile skies.

From the period immediately following the end of World War II, to the gradual supremacy of the orbiting satellite, the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in a protracted, frequently tense, and often deadly, struggle to collect intelligence on Soviet air defense capabilities (for the U.S.) or resist efforts to collect such intelligence (for the Soviets.) The United States deemed the collection of such intelligence vital. From about 1946 to the early 1960's, before the era of the nuclear-tipped missile, the sole means by which the United States could deliver an atomic weapon on a target in the Soviet Union was by long-range bomber. To do so required that the bombers be able to penetrate Soviet air defenses. And to do that, it was vitally important that the United States have up to date intelligence on Soviet air defenses; on Soviet air defense technology (radar systems, missile systems, etc.), on the layout of forces arrayed to defend Soviet air space, on the exact locations of potential targets, and the overall ability of the Soviet forces to respond to the incursion of U.S. aircraft. And as we learn in the book, until the development and deployment of such aircraft as the U-2 and the SR-71, the United States military and intelligence agenices relied on a stop-gap system of converted and redesigned WWII or Korean War era bombers, cargo transporters and combat aircraft to provide such intelligence. Unfortunately such a system, and the critical importance of obtaining such intelligence, made for extremely hazardous conditions for the men whose job it was to man these aircraft.

Where Burrows' book is most enjoyable is the way in which he recounts some of the individual reconaissance missions that these men carried out. In reading about their missions, we can almost imagine ourselves, sitting in the belly of a loud, slow and terribly vulnerable converted bomber, crammed full of electronic devices to collect radio and radar signals, but otherwise completely unarmed against more agile enemies that would seek to shoot it down. We imagine that bomber, suspended 36,000 feet in the air, driving hard over military targets deep in Russia, attempting to get the badly needed intelligence before Soviet fighters catch up to it and blast it from the sky. Most of the time these missions suceeded. Many times they did not. It was not uncommon for planes to simply disappear after suddenly aborted cries for help, their crews never to be seen or heard again, the men either killed outright or taken captive by Soviet, Chinese or North Korean forces, never to return to the United States. It was also not uncommon for these planes to return home, shot up and badly damaged, but their crews alive and unharmed. As often as these missions were routine, or even boring in some instances, they could just as suddenly turn violent and deadly.

But Burrows' book isn't simply a recitation of individual stories of tragedy and heroism. He also surveys the entire data gathering effort from inception to the present day, helping us to understand why U.S. leaders and military commanders would push their men to take such awful risks in the face of gnawing worry as to Soviet capabilities to launch a nuclear strike. He describes for us how the program began on a shoe-string, sometimes with instruments carried by hand into the planes by the crews that would man them, and how it eventually culminates in the development of the SR-71 (not one of which was lost to enemy action) and satellites that roam far above the Earth.

Burrows is not without his own opinions however. And one theme that dominates this book is what in many instances has amounted to a betrayal of the men who served their country by going on these dangerous missions. Without question, the surveillance operations that the United States carried out against it's cold war enemies put it in an awkward position. On the one hand, airmen and intelligence operatives were being asked to take tremendous risks to "ferret" out Soviet capabilities, and many were lost or taken into captivity as a result. On the other hand, the fact these operations were supposed to be conducted in secret, and that the loss of any aircraft was a propoganda opportunity for the enemy, led U.S. leaders to in most instances simply flat-out deny that such surveillance was taking place. Whether a plane was shot down over international waters or deep in enemy territory, the story was always the same; they were engaged in routine "weather monitoring" or scientific research, or the aircraft was blown into enemy territory by bad weather, or pilot error. This was the story told to the public, and to the families of the men who died or were taken captive on these missions. This meant there was the potential for embarassment if any of the men in the mission turned up alive, or their bodies were recovered such that the true cause of their death could be discovered. As a result, U.S. military commanders and political leaders frequently found it convenient to not push the issue of recovering the bodies of the dead pilots or crews, or even the return of those taken captive. Burrows recounts several credible stories of pilots and intelligence personnel who managed to survive the shooting down of their aircraft only to be taken captive by Soviet, Chinese or North Korean forces. In only a few high profile instances such as with Gary Powers, the U-2 pilot shot down over the Soviet Union, where the capture was trumpeted for propoganda purposes, did the United States seek the return of the captured personnel. Otherwise, they were quite simply forgotten, even as reports emerged that these men were put on trial and imprisoned in their captors country, or executed. Certainly, the question of what to do with men who were captured, or whose bodies were recovered by the enemy, was a difficult one, and it can be argued that these men went into their missions knowing what they signed on for. But what cannot be excused are the lies that were frequently told to the family members of the men who were captured or died executing these missions, lies told even long after the purpose for the lies had faded away. In one particularly galling portion of the book, Burrows recounts for us the commission set up in the early 90's to investigate and cooperate with the new Russian government in determining the fate of many of these men. Once it became clear that it benefitted both sides to simply let the matter drop, both sides backed away from their efforts, and U.S. military commanders continued to feed misinformation and outright lies to the families of the men who were lost. Burrows' sense of outrage over this treatment comes through clearly in the book, and he points out to the reader that there were many times when such secrecy seemed not to serve national security or the interests of the United States, but rather the interests of U.S. military personnel and leaders who didn't want their past mistakes brought to the light of day.

Overall, "By Any Means Necessary" is an excellent book that greatly illuminates a portion of the cold war that was anything but cold. Like the soldiers who fought our enemies on the ground, on and the sea and in the air during the cold war, these men also fought a war of their own, though a "shadow" war whose casualties could not be known or mourned. They served with distinction and with honor, all the moreso for their sacrifices they made in secret, without the public adulation they also deserved, and Burrows does a fine job of bringing their heroic efforts to the light of day after so many decades of secrecy.

1 comment:

The Cold War is an era that is quickly being forgotten about, and because of the secrecy surrounding the not-so-cold parts of the war, much of the substance of it will never be known. It's a sad thing that so many men in our armed forces (and the other side's too) died and were forgotten without the proper appreciation of their countries.

Most of what's known and written about the Cold War deals with the great events, like the Cuban missile crisis, or the fall of the Berlin Wall, or the great airlift at the beginning of the Cold War. All momentous events, to be sure, but that was not the extent of the cold war. Americans probably only think of the Vietnam war when they think of any wars that the Cold War spawned, but in reality we were in dozens of conflicts around the world, from South America to Africa, to the Middle East (Afghanistan was a part of that), to Southeast Asia.

A lot of people died because of the Cold War, and it seems that for the most part they'll be forgotten because of the "big picture" focus that we always seem to get on the events of the Cold War. It certainly should be a larger part of American history, as it is definitely responsible for much of the shape of the world as it is now.

Post a Comment